Introduction

The global history of broadcasting policy has

shown that government monopoly over broadcasting sector is no longer viable in

many countries. Along with the state and/or public service television,

commercial TV stations has grown significantly to provide services for their

customers (Collins, 2008). On the other hand, it has been argued that broadcast

frequency is considered as public’s good and exists in public domain (Flew, 2006). In this context, the idea of public service

obligation for all broadcasting companies arises and persists. Therefore, the

commodification of the public’s good has been put into questions: how commercial

TV station could gain profit without violating the public interest? And how commercial

TV station could gain profit while at the same time fulfill its public service

role? Under these questions, broadcasting law becomes relevant and crucial.

Information is the main commodity in

broadcasting industry as the commercial TV stations use the broadcasting

frequency ‘to inform’ their viewers in a way to attract viewers for their

business goals. As the information is nationally broadcasted, national

information goals have been stipulated within national broadcasting law to become

the standard measure of ‘information appropriateness’ However, a fundamental question

emerges: are national information goals compatible with commercial TV stations’

goals?

In this essay, I will argue that national

information goals are incompatible with the aims of commercial TV stations. The

goals are served better by public service broadcasting institution. Therefore,

I will suggest that providing and supporting public service broadcasting is

crucial to fulfill the national information goals. To support the argument, I

will elucidate the brief history of Indonesian TV broadcast. I will also explain

how Indonesian commercial TV stations tend to be profit-driven and frequently

violate the national information goals as stipulated in Indonesian Broadcasting

Law number 23/2002 and Broadcasting Code of Conduct and Broadcasting Programs

Standard (P3SPS).

Indonesian Broadcasting Law states that

broadcasting is aimed to strengthen national integrity; to cultivate national

character and identity which is based on faith and piety (to God); to educate

the nation; to promote prosperity; to develop the independent, democratic, just,

and prosper society; and to grow Indonesian national broadcasting industry. It also

states that broadcasting is a medium to inform, to educate, to provide healthy

entertainment, to control society and to promote social cohesion. It also

states that broadcasting has economy and cultural functions (Indonesia, 2002).

Methodology

I will focus my discussion only on

television, thus avoid a rigor discussion on other media such as radio, digital

media (internet based media), printed media (magazine, tabloid, and newspaper),

and cinema. I choose television as it is considered the most popular media in

Indonesia with urban penetration rate reached 100 % in 2012. The rate was far

beyond other media penetration rate in the same year such as internet with 57%,

newspaper 55%, radio 40%, magazine 12%, and cinema 11% (Statista, 2013).

To support my thesis, I will look at Indonesian

Broadcasting Commission (KPI) investigation over Indonesian broadcasting

materials (programs) from 2010 to 2012. For the latest update, I will particularly

examine some violations on Indonesian national commercial TV stations’ programs

that was broadcasted on 9 – 23 July 2013. My examination will be

based on KPI’s report as it was issued

by the legitimate independent body which was set up to regulate Indonesian

broadcasting sector, including overseeing broadcasting content (Kitley, 2008). In overseeing the content, KPI refers to P3SPS

(KPI, 2010).

Discussion

Indonesian broadcasting history: from the dominance of the state to the market

If we look at the history of television broadcasting

sector in many countries, we can see that its emergence was mostly initiated by

the government or the state, such as the BBC in the UK, ABC in Australia, and CBC

in Canada. In Indonesia, Televisi Republik Indonesia (TVRI) was launched by the

Indonesian government on 24 August 1962. Its main agenda was to support the

state interest (TVRI, 2013).

The idea to establish a TV station was

introduced in 1953 by Maladi, Indonesian Minister for Information, to support

the first Indonesian general election in 1955. Subsequently, the idea was

rejected by Indonesian cabinet (comprised of president and ministers) as the

project was viewed too expensive. The idea was finally approved in 1958 as

Indonesia was about to host the fourth Asian Games in 1962 (SK, 2012). The establishment of TVRI was part of the

first Indonesian president Sukarno’s mercusuar

political vision in which national pride is much more important than any other

agendas. TVRI, he believed, could increase Indonesian image in the world (Pahlemy, 2007).

The opening of the fourth Asian Games was

broadcasted for three hours for the radius of 70 kilometers. The live program

was received by 10,000 televisions set which was randomly distributed for free

around Jakarta (SK, 2012). The program also reached Bandung (about 200

kilometers away from Jakarta) as students at Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB)

and some local engineers set up a relay station so that Bandung people could

also watched the event. The effort made by students and engineers in Bandung has

given three important lessons:

- promoting the spirit of national unity;

- declaring an idea of Indonesia self-sufficiency on broadcasting technology;

- enabling the development of new business sectors, such as the development of relay transmissions all over the country and television set selling (Barker, 2005).

A major progress occurred in 1976 when

Indonesian government launched Palapa satellite. Indonesia became the first developing country

in the world that had its own satellite (Barker, 2005). The satellite was used as a mean to unite thousands

of Indonesia’s sprawling islands across the country from Sabang in the far-East

to Merauke in the far-west. It brought into reality the idea of the unity of

Indonesian people as a nation, the imagined community (Kitley, 1994). This idea is clearly reflected through the

name of the satellite: Palapa. The name was chosen by Suharto, the president of

Indonesia, to project his political vision.

I pondered the history of [the Kingdom of] Majapahit

when [its] Prime Minister Gajah Mada vowed that he would not taste the fruits

of his efforts (Palapa) before the unity and integrity of the kingdom had

become a reality. Today, this unity and integrity are living realities. (Abdullah, 2009: 436)

TVRI monopoly ended in 1987 as a result of

continuing demand by the business sector to commercialize broadcasting sector

and to provide alternative viewing for the public (Kitley, 1994). During 1987 to 1993, five commercial

television stations had been established: Rajawali Citra Televisi Indonesia

(RCTI) in 1987; Surya Citra Televisi Indonesia (SCTV) in 1989; Televisi

Pendidikan Indonesia (TPI-now MNCTV) in 1990; Andalas Televisi (ANTV) in 1993;

and Indosiar in 1995. The period was called as the first wave of Indonesian

commercial television (Hollander et al.,

2009, Hendriyani et al.,

2011).

A distinct characteristic of the first wave

of commercial television in Indonesia is that the stations were still deeply-controlled

by the Suharto regime (Hollander et al.,

2009, Sudibyo and Patria,

2013). The state prohibited other TV stations than

TVRI to produce news program with strong political views. Therefore, only soft

news program could exist. The government could also interfere the TV stations’ editorial

policies. Based on Guidelines for Commercial Television (1990), they should support

the Constitution, Pancasila (state’s ideology), national development, and SARA doctrine (abbreviation for suku or ethnic group, agama or religion, ras or race, and antar-golongan

or inter-group relation) (Hollander et al.,

2009). However, despite the ideal goals, the

regime was free to define what was considered against those rulings. This kind

of political approach was easily implemented as those TV stations were owned by

Suharto’s cronies (Hollander et al.,

2009, Sudibyo and Patria,

2013). This phenomenon was identified as ‘a

process of commercialization without independence’ (Chan and Ma, 1996:

49).

The second wave of commercial broadcasting in

Indonesia occurred during the earliest period of Reform era, after the collapse

of the Suharto regime in 1998 (Hendriyani et al.,

2011). State control over broadcasting

institutions became unpopular. In 1999, Department of Information, who strongly

regulated the broadcasting sector, was dissolved (it was re-established in 2001

with new name “Department of Communication and Information Technology”). Within

two years (2000-2002), Indonesian government issued five new licenses for five

new commercial television stations: Metro TV, Trans TV, Global TV, TV 7 (now Trans

7), and Lativi (now TV One). A distinct characteristic of the second wave is

that the owners of the commercial TV stations were diverse, came from different

backgrounds, and had no close relationship with the ruling elites (Hollander et al.,

2009). Therefore, the commercial TV stations after

the collapse of Suharto regime (the Reform era) are free from government intervention.

As the competition in the broadcasting sector

increased, TVRI faced uncertain status. To address this matter, in 2000, the Indonesian

government issued regulation number 36/2000 which changed the status of TVRI from

foundation to commercial TV station owned by the government under the Ministry

of Finance (TVRI, 2013). The status is called Perusahaan Jawatan (Perjan). Under this regulation, TVRI was funded

from the National Budget (Anggaran Pendapatan dan Belanja Negara/APBN), license

fee, commercial TV contribution, cooperation with other stakeholders, and other

legal businesses (Indonesia, 2000).

This

status was short-lived and ended in 2002. The government changed TVRI status

from Perusahaan Jawatan to Perusahaan Perseroan (Persero), thus

TVRI was fully commercialized. It no longer works under the Ministry of Finance

but under the Ministry of State-owned Enterprises (Kementerian Badan Usaha

Milik Negara/BUMN). However, this status was also short-lived. The new Indonesian

Broadcasting Law (IBC) that was enacted in 2002 states that TVRI should fully

operated as public service broadcasting institution by 2005 (TVRI, 2013). However, the source of funding is almost

the same as it was. Based on the law, TVRI is funded by five major sources: (1)

license fee; (2) National/Provincial Budget; (3) public donation; (4)

advertisement; and (5) other legal related broadcasting businesses.

Despite its clear status as a public broadcasting

institution, TVRI still cannot compete with other commercial TV stations. TVRI

has consistently gained the lowest market share despite it has the widest

coverage region in Indonesia (Hollander et al.,

2009). Low budget support from the government; lack

of qualified human resources; and old infrastructure are the most highlighted

sources of the problem (Pahlemy, 2007, Batubara, 2012, Nurhasim, 2012).

Although TVRI is allowed to generate funding from other sources, TVRI operational

budget merely relies from national budget. The allotted budget is considered

too small to support TVRI daily operation although the budget has continuously

increased every year. It has been argued that in 2011-2012, TVRI budget was about

a third of the commercial television market leader (Batubara, 2012).

|

| Figure 3: Indonesian TV stations market share 2007 (Hollander et al., 2009) |

|

| Figure 4: Indonesian TV stations market share 2013 (Research, 2013) |

|

|

|

Figure three and four show that the commercial

TV stations have absolutely taken over TVRI’s dominance. If we compare the 2007

figure with the 2013 figure, it also shows that competition has increased

significantly. Market share disparity between TV stations is getting narrower, although

TVRI still has the lowest market share.

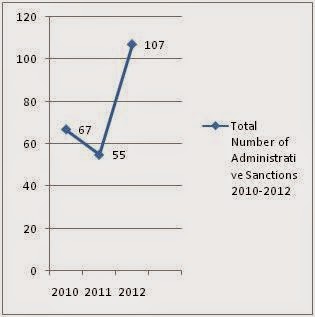

However, the commercial TV stations’ achievement

does not correspond to their programs quality as stipulated by the law and

regulations. KPI reports over the issue have shown that the quality of commercial

TV stations’ programs has deteriorated. From 2010 to 2012, KPI had issued 229

administrative sanctions. The majority of those violations were conducted by

commercial TV stations.

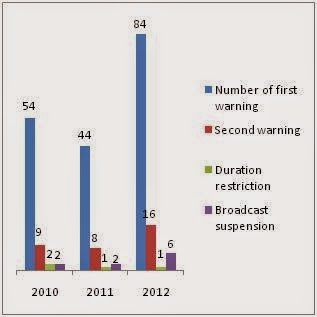

Based on P3SPS, there are seven

administrative sanctions (KPI, 2012a): (1) warning letter; (2) broadcast

suspension; (3) duration restriction; (4) administrative fine; (5) broadcasting

ban; (6) discontinuation of broadcasting permit by the end of the current

license; and (7) termination of the current license. However, there were only

four administration sanctions imposed in 2010-2012 (KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011, KPI, 2012b): (1) first warning; (2) second warning; (3) duration

restriction; and (3) broadcast suspension.

|

|

|

| Figure 6: Administrative sanctions based on categories 2010-2012(KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011, KPI, 2012b) |

|

| Figure 7: Number of administrative sanctions based on TV stations 2010-2012 (KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011, KPI, 2012b) |

From 2010 to 2012 there had been 228

administrative sanctions. The average number of sanctions in for commercial TV

stations in a year stands at 7.4, while TVRI stands at 1.6. It clearly suggests

that the commercial TV stations are more frequent to breach broadcasting rules.

I would like to argue that it happens as the former is much more focus on

making money, while the latter is much more focus on public service merit. As a

result, those two types of TV stations are heading to the opposite directions. It

can be understood as the commercial TV stations mainly generate their revenues from

advertisement, while TVRI’s budget comes from taxpayer’s money. Therefore, TVRI

can be much more focus to produce programs (despite their budget, human

resources, and infrastructure constraints) and fulfill its public service

mandate.

Pornography on the top list

Based on KPI’s report, most violations are related

to pornographic materials, child protection, violence, swearing and cursing,

program classification, modesty and decency, privacy, mystical-horror-supernatural

material, religion issues, journalism ethics, individual/communal harassment, and

gender issues (KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011, KPI, 2012b). Among those violations, restriction on pornography

was the most violated one in 2010-2012. It dominantly breached Broadcasting

Programs Standard, article 17a (SPS 2009) or article 18 (SPS 2012). The article

states that broadcasting programs are prohibited “to exploit human body that

could arouse lust, such as: thigh, back, breast, and/or genitals” (KPI, 2009). There had been 1012 violations from June

2010 to December 2011. The majority of the violations were conducted by

commercial TV stations with average of 33.3 violations in a semester. On the

other hand, TVRI’s violation in a semester was 0.33 (KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011).

|

| Figure 8: Number of violations on pornography June 2010 - December 2011(KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011) |

|

| Figure 9: Total number of violations on pornography June 2010 - December 2011(KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011) |

|

| Figure 10: Percentage of the total violations on pornography June 2010 - December 2011 (KPI, 2010, KPI, 2011) |

Violations during fasting month: a closer look

I have examined that from 9 to 23

July 2013, KPI had issued eight administrative sanctions to six programs

from four commercial TV stations: Trans TV (four sanctions); ANTV (two

sanctions); Trans 7 (one sanction) and RCTI (one sanction). Most of the programs

were broadcasted on prime-time hour with relatively high rating. Five of eight

violations broadcasted on prime-time hours, while three of eight violations

occurred when the programs was the market share leader during the broadcasting

hours.

The two week period coincided with the Ramadhan

month based on Islamic calendar. During that period, the majority of Indonesian

Muslims conducted fasting which is obligatory in Islam. To conduct the fasting,

they get up earlier (around 2-5 am) to have an early-meal before sunrise. As a

result, that period became ‘busy hours’ and all Indonesian TV stations

considered it as one of prime-time hours in Ramadhan. There are three prime-time

periods: 6 – 9 pm, 9 – 11 pm, and 2.30 – 4 am. The prime-time is defined by the

highest rating and average number of viewers from all TV channels (Hasan, 2013).

|

TV station

|

Program

|

Schedule

|

Sanction

|

Violation

|

Rating

|

Share

|

|

Trans TV

|

Yuk Kita

Sahur (Lets have early meal)

|

23 July

2013, 2 – 4 am

|

2nd

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition, certain

sexual orientation.

|

3.3

|

30.9 %

|

|

12 July

2013, 2 – 4.15 am

|

1st

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition, certain sexual

orientation.

|

2.1

|

17.2 %

|

||

|

|

Karnaval

Ramadhan

(Ramadhan

Carnival)

|

15 July

2013, 4.15 – 5.15 pm

|

1st

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition, certain

sexual orientation, breach of child protection.

|

1.4

|

7.8 %

|

|

|

Ceriwis

Pagi Manis

(Sweet

morning chat)

|

13 July

2013, 9.15 – 9.45 am

|

2nd

warning

|

violation

of decency norms, child protection, broadcasting category

|

1.1

|

9.4 %

|

|

ANTV

|

Sahurnya

Pesbuker

(Facebookers’

early-meal)

|

23 July

2013, 2 – 4.30 am

|

2nd

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition, breach of

child protection, and violation of decency norms.

|

0.7

|

6.1 %

|

|

|

Sahurnya

Pesbuker

(Facebookers’

early-meal)

|

10 July

2013, 2 – 4.30 am

|

1st

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition, breach of

child protection, and violation of decency norms.

|

1.1

|

8.5 %

|

|

RCTI

|

Hafidz

Indonesia (Mastering [Holy Quran] Indonesia)

|

9 July

2013, 2.30 – 3.30 pm

|

1st

warning

|

Violation

of child protection and decency norms.

|

2.5

|

20.2 %

|

|

Trans 7

|

Sahurnya

OVJ (OVJ’s early-meal)

|

12 July

2013, 2.15 – 4.30 am

|

1st

warning

|

Harassment

to someone and/or group with certain mental and physical condition and

violation of decency norms.

|

2.5

|

19.3 %

|

Conclusion

Based on those findings, I conclude that

national information goals are incompatible with the aims of the commercial TV

stations. This conclusion is based on the facts that most of the violations of

broadcasting rules conducted by commercial TV stations’ programs. There is an

indication that the more profitable the program is, the more prone the program

violates the broadcasting rules. On the other hand, it also shows that only news

commercial TV stations are less-prone to violate the rules, such as Metro TV

and TV One. It also finds out that TVRI, the public service broadcasting television

in Indonesia, has consistently had the lowest number of violations. The latter

finding suggests that national information goals are much more possible to be

implemented by public service broadcasting institution. Therefore, I suggest

that supporting and strengthening the institution, among others by providing

more budget, is the most effective way to ensure national information goals to

be achieved.

References

INDONESIA, T. P. O.

2002. Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 32 Tahun 2002 tentang Penyiaran. In: GOVERNMENT, I. (ed.). http://www.kpi.go.id/download/regulasi/UU%20No.%2032%20Tahun%202002%20tentang%20%20Penyiaran.pdf: Komisi Penyiaran

Indonesia (Indonesian Broadcasting Commission).

KPI 2010. Laporan Akhir

Tahun 2010 Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia. http://www.kpi.go.id/index.php/laporan-akhir-tahun.

KPI 2011. Laporan Akhir

Tahun 2011 Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia http://www.kpi.go.id/index.php/laporan-akhir-tahun.

KPI 2012b. Dinamika

Penyiaran 2012 Refleksi Akhir Tahun KPI Pusat. http://www.kpi.go.id/index.php/siaran-pers-1/31021-dinamika-penyiaran-2012-refleksi-akhir-tahun-kpi-pusat: Komisi Penyiaran

Indonesia.

POHAN, R. 2012. Dinilai maju pesat, anggaran TVRI dinaikkan

1,7 Trilyun [Online]. http://ramadhanpohan.com/artikel/926-dinilai-maju-pesat-anggaran-tvri-dinaikkan-17-trilyun-: http://ramadhanpohan.com/. [Accessed 29 August 2013].

SK, I. 2012. TVRI Mau ke Mana? [Online]. http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2012/08/24/02041514/TVRI.Mau.ke.Mana.: Kompas. [Accessed 28 August 2013].

STATISTA 2013. Media

penetration in urban Indonesia from 2009 to 2012. January 2013 ed. http://www.statista.com/statistics/251462/media-penetration-in-urban-indonesia/: eMarketer.

TVRI. 2013. Sejarah [Online].

http://www.tvri.co.id/index.php/perihaltvri/sejarah: TVRI. [Accessed 28 August 2013].